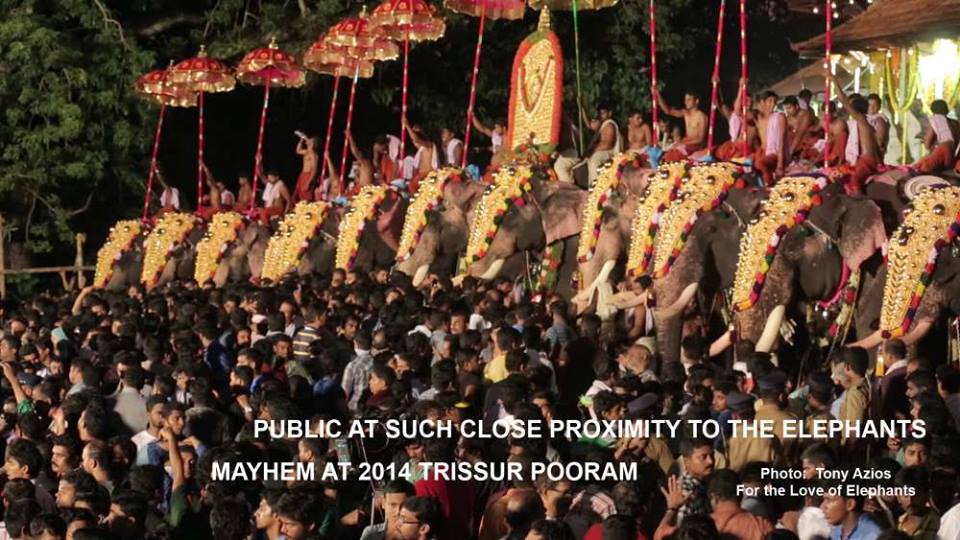

Temple and festival elephants were drowning in a sea of sadness as the masses gathered in the thousands to celebrate the annual Trissur Pooram in Kerala, India — the largest congregation of male elephants in the world. More than 90 elephants took turns during a 36-hour festival to entertain the insane crowd, mostly drunk and occasionally drenched by sudden downpours.

These elephants were transported from temples across Kerala in trucks through bumpy rugged roads from as far as Trivandrum, more than 300 kilometers from Trissur, over an eight-hour journey in the kind of odd weather that the southern state experienced during this year’s festivals. No food, no water, no sleep for these poor souls during the journey, although they tend to graze between 16-18 hours everyday.

Heavens opened up just 48 hours before the main festival, as though the elephant God, Lord Ganesh was weeping over the torture of his species. Fortunately the grey monstrous clouds hovering over the processions provided the much needed shade for the gentle giants. It was hot, hazy and humid with temperatures hovering between 40 and 45 degrees Celsius, and the deafening sounds of the music and fireworks were agonizing.

It’s been almost a week since my return from Kerala where we were filming my documentary For the Love of Elephants, to expose the abhorrent torture behind the glitz and glamour of Trissur Pooram. And although I have recovered from the jetlag, I’m having a hard time disembarking from the emotional roller coaster ride.

I’m haunted by the images of one particular elephant whose rear limbs were so badly injured that he was limping along the procession. It seemed that the raw wounds were intentionally inflicted, as the two handlers and the owner desperately tried to cover the injuries and block our camera several times (although they were unsuccessful).

To be sure, government veterinarians conducted a routine health-check on participating elephants prior to the commencement of the festival. But when I asked about the injured elephant, the chief vet said, the wounds weren’t serious enough to disqualify him from the festival, adding that their primary focus was to detect musth. This is an annual cycle that causes an increase in testosterone and energy levels, which the elephants typically exhaust in the wild by wandering, fighting off bulls and mating. However, in captivity they are unable to burn off all those energy reserves, and so they become aggressive and dominant, most times resulting in stampedes, human deaths and elephant torture.

Clearly the vets can’t allow this to happen as too much money is at stake for the owners, the mahouts, the brokers and of course the hoteliers, as tourism was booming with some mediocre hotels charging as high as $500 per night. These business men know all too well that the elephants are the main attraction, but what they don’t seem to realize is, without giving proper care and attention to the cash cow, it could collapse, bringing down with it their business also.

And here’s the perfect recipe for such a calamity. It’s a scene that replays in my mind, a rude awakening I had at 3:00 a.m. on May 9. The deafening sounds of the earth-shattering high decibel fireworks that shattered my hotel’s bathroom windows that also exploded the festival temples’ roof tiles, damaging a prominent 200-year-old archaeological structure.

Research shows that such powerful explosions are sure to spook the elephants, as their feet, ears and legs are super sensitive to vibrations. According to this video, elephants can detect slightest ground vibrations caused by other animals using the soles of their feet.

“Elephants can hear low frequency sounds indistinguishable to humans. According to one theory they can detect lightning that strikes five kilometers away. It was reported that elephants quickly escaped to high ground after the Sumatra earthquake as they knew tsunami was coming.”

Studies conducted by UCLA’s Peter Narin suggest, “pressure-sensitive nerve endings in the elephants’ feet and trunks are other pathways for detecting the vibrations”

But unfortunately no escape for the two blind elephants that were tethered beneath a shed, just 400 metres from the fireworks display, all four legs shackled, making it impossible for the poor animals to even shift their bodies by the startling sounds of the fireworks.

Now, using blind elephants in festivals is nothing new in Kerala. We were informed by an undercover researcher that the majority of the elephants in that state are blind, but when I asked the government veterinarian, his response was, “only 10 percent of them are blind.” Even if it’s just 10 percent, isn’t it unconscionable and unpardonable to exploit these vulnerable animals? In my view, this is one of the worst kind of atrocities against such an intelligent animal. How sad!!

There’s lots to be said about the extent of cruelty that elephants are having to endure year after year during Trissur Pooram festival. In the coming days I will share my observations and documentation of the most basic humane and welfare guidelines that are being ignored in the name of culture and religion, as well as offer alternatives as suggested by world renowned elephant experts.

I will be also unpacking my soulful journey to India, featuring some of our key supporters who wholeheartedly and unconditionally dedicated their time, and energy in helping us achieve our funding goal and raise just over $40,000. We were able to travel to India and gather close to 100 hours of footage because of their generosity. The real work has just begun!

Meantime, there’s a groundswell of hope for temple elephants, as more and more people are waking up to the atrocities, and raising their voices — collective voices that are becoming hard to ignore. The fact that people from all walks of life — strangers, artists, elephant and animal lovers from around the world came together in solidarity in the making of the film For the Love of Elephants is proof that people are standing up for these magnificent animals. I’m hopeful that the release of our film will produce positive results for all stakeholders, mainly for India’s Heritage Animal.